Much of Greek Mythology reflects the daily activities that took place in people’s lives. Female symbols such as the hearth and the loom were reflected in the goddesses Hestia and Athena respectively. Craftsmanship was linked more generally with the master maker god Hephaestus. This article examines the myths about weaving and threading. Athena herself features in those myths, as do several well-known women from Greek mythology, including Arachne, Penelope, Philomela, and Ariadne.

Greek Mythology’s Threading Contest: Athena vs. Arachne

Many ancient Greek stories involve seamstresses, but only one story features a contest between two of them: the story of Arachne. It involves another formidable seamstress, the goddess Athena, whose mastery of weaving made her the protectress of weavers and, by extension, all handicrafts. This quality of Athena is expressed in one of her many epithets: Ergane, meaning industrious.

The ritual act of weaving was an important part of the goddess’ cult. Each year the woven peplos (long garment) for her statue on the acropolis was replaced and every four years a giant peplos displaying myths and stories was made for her statue, paraded during the Panathenaea festival.

In Greek mythology, Arachne, a pupil of Athena, was so skilled at her art that she challenged the goddess, who produced a tapestry showing the gods in their majesty. Arachne unwisely chose to depict the gods’ amorous adventures, and Athena, either affronted by the skill of her work or by her choice of subject matter, tore her work to bits. In despair, Arachne hung herself, after which Athena took pity on her, and turned her into a spider (arachne is Greek for spider).

Philomela’s Transformation

In another weaving story, Philomela, who is described as a skilled weaver, is turned into a nightingale. However, the transformation is performed by the gods for her protection. After either tricking her into a sham marriage or raping her (there are various versions), King Tereus imprisons her and cuts out her tongue to prevent her from revealing the truth, but she embroiders a message to her sister Procne and they manage to escape. Tereus pursues them with an axe but they are saved by being transformed into birds. The most well-known versions of these tales have been preserved for us in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (AD 8), a collection of narrative poems concerned with transformation.

Penelope’s Shroud

Two other famous weavers, Ariadne and Penelope, manage to use thread to protect their loved ones by combining cunning as well as skill in their use of their craft. In Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope weaves and unweaves a shroud in her palace as she waits for Odysseus to return from Troy, putting off the day when, assuming he is dead, she will have to remarry.

After devising numerous strategies to delay her suitors finally she resorts to claiming that she is finishing the funeral shroud of Odysseus’ father, Laertes, pacifying them with the words, ‘Young men, my wooers, since goodly Odysseus is dead, be patient, though eager for my marriage, until I finish this robe—I would not that my spinning should come to naught—a shroud for the lord Laertes, against the time when the fell fate of grievous death shall strike him down; lest any of the Achaean women in the land should be wroth with me, if he, who had won great possessions, were to lie without a shroud’ (Hom. Od. 2.95ff., transl. A.T. Murray).

For three years she works on the shroud, secretly undoing at night what she has done during the day. As old Laertes had previously won glory as one of the Argonauts, one of the highest accolades for ancient heroes, and had also participated in the hunt of the Calydonian boar, it would be intriguing to know what she might have chosen as the subject matter for the shroud. Sadly, Homer speaks nothing of it. Fortunately for Penelope, as the patience of the suitors is running out and they discover her ploy, Odysseus returns in the nick of time to slay them all and reclaim his kingdom.

Incidentally, an early version of the nightingale myth of transformation appears in the Odyssey when Penelope relates the myth of Aëdon to Odysseus who is in disguise as a beggar. Aëdon is turned into a nightingale (aëdon in Greek) by Zeus to relieve her grief after she has killed her son by mistake. Penelope uses the story to express the fear of a mother for the safety of her child. (Hom. Od. 19.515ff.).

Weaving was such an important part of life that it was common practice for female members of the royal household to work on the loom. Penelope’s cousin, Helen of Troy is shown in Book 3 of the Iliad occupied in her work on a long garment: ‘She [Iris] found Helen in the hall, where she was weaving a great purple web of double fold, and thereon was broidering many battles of the horse-taming Trojans and the brazen-coated Achaeans, that for her sake they had endured at the hands of Ares’ (Hom. Il. 3.125ff., transl. A.T. Murray).

Similarly, other female characters in the Odyssey are depicted weaving, such as the enchantress Circe, who sings while she works at an enormous loom, and the nymph Calypso who is weaving when Hermes tells her that she has to let Odysseus go, after keeping him trapped for seven years on her island.

Ariadne’s Thread

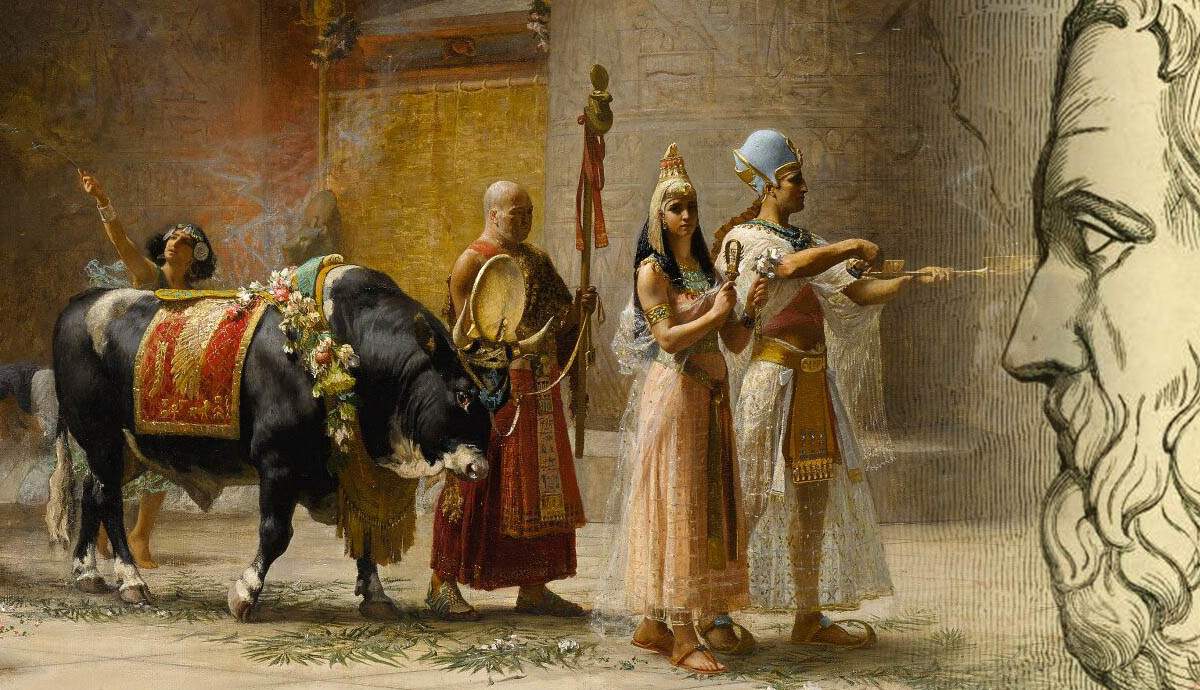

Ariadne is most famous for helping Theseus overcome the terrors of the Cretan Labyrinth wherein dwelt the fearsome Minotaur, half-man half-bull. Ariadne was put in charge of the Labyrinth by her father King Minos. But, because she falls in love with Theseus, when he is sent to his death within the maze she provides him with a sword to kill the beast and a ball of spun thread to lay a trail so that he can find his way out again. The labyrinth was the work of Daedalus, who Homer also mentions as the creator of a dancehall for the Cretan princess:

“Therein furthermore the famed god of the two strong arms cunningly wrought a dancing-floor like unto that which in wide Cnosus Daedalus fashioned of old for fair-tressed Ariadne”

(Hom. Il. 18.590, transl. A.T. Murray).

Thread, Clothing, and Destiny

The skill of the seamstress was revered in the ancient world, and stories from Greek mythology reflect its importance. The thread of life itself was spun on the distaff by the Moirai, the three Fates or crones who control destiny, and in the myths, the act of weaving utilizes the importance of storytelling and cunning.

Homer, Ovid, Apollodorus, and many other authors have given these weaving heroines of myth pride of place in their work. Myth often contrasts the wilderness with notions of civilized behavior. In both myth and reality, shepherds in the mountains who wore animal skins while working on the loom were a signifier of civilized life within the city.

Scholars have noted the importance of clothing in the works of Homer both in terms of signifying status and asserting identity. His depictions are precise, including the lovely description of fair Helen as tanypeplos – long robbed. Visually, the seamstresses are often shown with their tools. The most common example is that of Ariadne, carrying her symbol, a ball of thread, on her person, much like the spindle of the goddess Clotho, one of the three Fates.

Tales of Ancient Seamstresses Retold

The stories of Ovid, including those of Arachne and Athena, and Philomela and Procne, were particularly influential during the Renaissance. Arachne is mentioned by Dante, and Philomela’s story triggered a rich response, with poets from the Elizabethans to Keats inspired by the beauty of her singing.

Philip Sidney expresses the anguish of Philomela perfectly in his poem The Nightingale or Philomela:

The nightingale, as soon as April bringeth

Unto her rested sense a perfect waking,

While late bare earth, proud of new clothing, springeth,

Sings out her woes, a thorn her song-book making,

And mournfully bewailing

Philomela was the inspiration for Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale, a poem overshadowed by his grief for his dead brother Thomas. He calls the nightingale “immortal”, alluding to Philomela avoiding death by being transformed into a bird by Zeus: “Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!”

Modern poets and writers too have found inspiration in these stories and created a number of engaging retellings. Two recent examples are The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood and Ariadne by Jennifer Saint.

Women’s Activities Depicted in Pottery

Weaving and threading are also depicted in art and notably in pottery. This Stamnos from Athens depicts a woman spinning thread between two other female companions. The Stamnos is attributed to Syriskos (fl. 480-460 BC), a skilled painter and potter mainly of red-figured vases in Athens, who also worked in the white-ground style. Stamnoi were used for mixing liquids and for storage.

Another red-figured jar, this time a hydria (water jar), shows three Athenian women engaging in a variety of quiet activities. This jar does not show weaving but has a similar display of quiet activities and companionship. It was created by the Chicago Painter — or “Painter of the Chicago Stamnos” — an Athenian artist who flourished in the middle of the 5th century BC. The Chicago Painter is known for the elegance and grace of his figures, something evident in this example and also in his name-vase, the Chicago Stamnos, held in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Arachne and the Seamstresses of Greek Mythology: Conclusion

The importance of weaving in the ancient world is highlighted by its prominent place in myth and legend. The goddess Athena herself was the protectress of weavers. The myth about her contest with the talented Arachne is only one of many fascinating stories about women who excelled in their craft and used their skill with ingenuity. Their stories live on in the pages of famous ancient literature, not least Homer, and some beautiful ancient depictions and modern art.