Postmodern art might be a term many of us are familiar with, but what does it really mean? And how, exactly, do we recognize it? The truth is, there is no one simple answer, and it’s a pretty broad, eclectic term encompassing lots of different styles and approaches, spanning from the 1960s to the end of the 20th century. That said, there are some ways of spotting postmodern tendencies in art with a little knowledge and practice. Read our handy list of postmodern traits that should make recognizing this loose art style a little easier.

1. Postmodern Art Was a Reaction Against Modernism

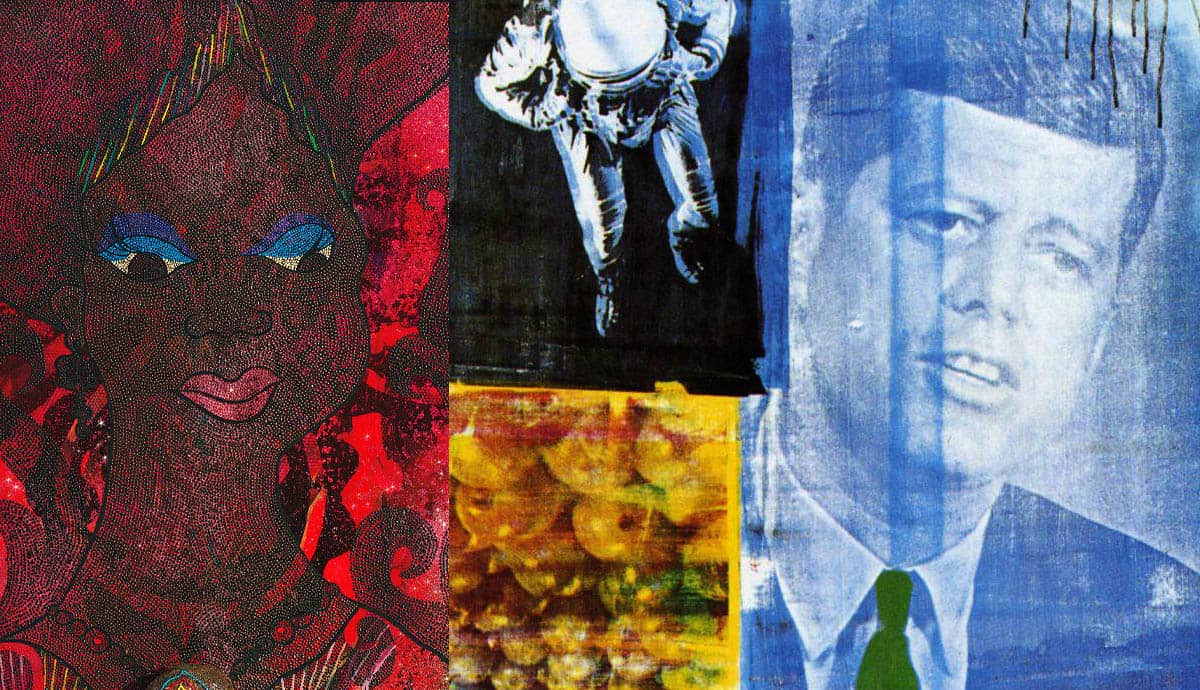

If modernism dominated the early 20th century, by the mid-century, things were beginning to change. Modernism was all about utopian idealism and individual expression, both of which were found by stripping art back to its simplest, most fundamental forms. By contrast, postmodernism tore all this to shreds, arguing that there was no such thing as a universal truth, and instead the world was actually pretty messy and complicated. So, postmodern art often has this really eclectic and multi-layered look to reflect this set of ideas – think Robert Rauschenberg’s screen prints, or Jeff Koons’s weird Neo-Pop collage paintings.

2. It Was Critical in Nature

In essence, postmodern art took a critical stance, picking apart the supposed idealism of modern society and urban capitalism with a cynical skepticism and sometimes even a dark, disturbing humor. Feminists rose to the forefront of postmodern art, critiquing the systems of control that had kept women in the margins of society for centuries, including photographer Cindy Sherman, installation and text artist Barbara Kruger, performance artist Carolee Shneemann and, perhaps most importantly, the Guerrilla Girls. Black and mixed-race artists, particularly in the United States, also stepped out into the limelight and made their voices heard, often speaking out against racism and discrimination, including Adrian Piper and Faith Ringgold.

3. Postmodern Art Was Great Fun

After all the high-brow seriousness and lofty idealism of modernism, in some ways the arrival of postmodernism was like a breath of fresh air. Rejecting the stuffy formalism of art galleries and institutions, many postmodernists took an open-minded and liberal approach, merging imagery and ideas from popular culture into art. The Pop Art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein might be seen as the earliest beginnings of postmodernism, and its influence was vast and far ranging. Following hot on the heels of Pop was the Pictures Generation including Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince and Louise Lawler, whose art was deeply critical of the popular culture imagery they parodied (but often in a ridiculous, shocking or exaggerated way, like when Cindy Sherman dressed up as a series of creepy clowns).

4. The Era Ushered in New Ways of Making Art

Many postmodern artists chose to reject traditional methods for making art, instead embracing the plethora of new media that was becoming available. They experimented with video, installation, performance art, film, photography and more. Some, such as the neo-expressionists, made multi-layered and richly complex installations with a whole mish-mash of different styles and ideas. Julian Schnabel, for example, stuck broken plates onto his canvases, while Steven Campbell brought together music, paintings and drawings that filled entire rooms with frenetic activity.

5. Postmodern Art Was Sometimes Really Shocking

Shock value was an important component in much of postmodern art, as a means of jolting the art audience awake with something entirely unexpected, and perhaps even completely out of place. The Young British Artists (YBAs) of the 1990s were particularly adept at this branch of postmodern art, even if they were sometimes accused of playing it for cheap thrills and the tabloid media. Tracey Emin made a tent stitched with names titled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, 1995. Then Damien Hirst chopped up an entire cow and its calf, displaying them in glass tanks filled with formaldehyde, ironically titling it Mother and Child Divided, 1995. Meanwhile, Chris Ofili stuck huge piles of elephant dung to his paintings in the manner of art, proving that with postmodernism, literally anything goes.