From the late 19th century through to the late 1950s, there was a huge industry in mass-produced tales of fiction in the United States. Cheap and engaging reading material in the form of horror, science-fiction, crime, war, sports, fantasy, western, sex, and romance was consumed by a literate working class looking for entertainment to pass the time. Through this phenomenon, famous authors and artists were born who would become giants in their field, attracting attention from huge audiences. This was the era of pulp fiction.

Before Pulp Fiction

It is often imagined that pulp magazines and pulp novels (“pulp fiction” as a general term) had their origin in the United States, and this may be true for the most part, but they were an evolution of events and products that had their start abroad.

The Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom created an increasingly literate working class. Along with the advancement of mass printing, this opened up new possibilities for entertainment that needed to be convenient and readily accessible. Literature could be consumed virtually anywhere, and the demand for reading material led to the creation of the “penny dreadful” – cheap weekly publications filled with stories of crime and horror. They were printed on inexpensive pulp paper and were significantly more affordable than serial novels by figures such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Charles Dickens.

By the 1860s, this trend found its way across the Atlantic to the heavily industrializing United States, where they were incarnated as “dime novels.” Originally, these dime novels were nothing more than reprints of published stories, but on much cheaper paper. As their popularity grew, however, new stories were written and published.

The Argosy & Subsequent Publications

Originally a magazine aimed at children and published starting from 1882, The Argosy was first published for an adult audience in October 1896 and quickly became extraordinarily popular. The cheap wood pulp paper meant that the publication could be larger for a fraction of the price of its contemporaries. In 1894, the magazine’s circulation was 9,000; after the format change in 1896, it was 80,000, and by 1907 the circulation had increased to almost half a million.

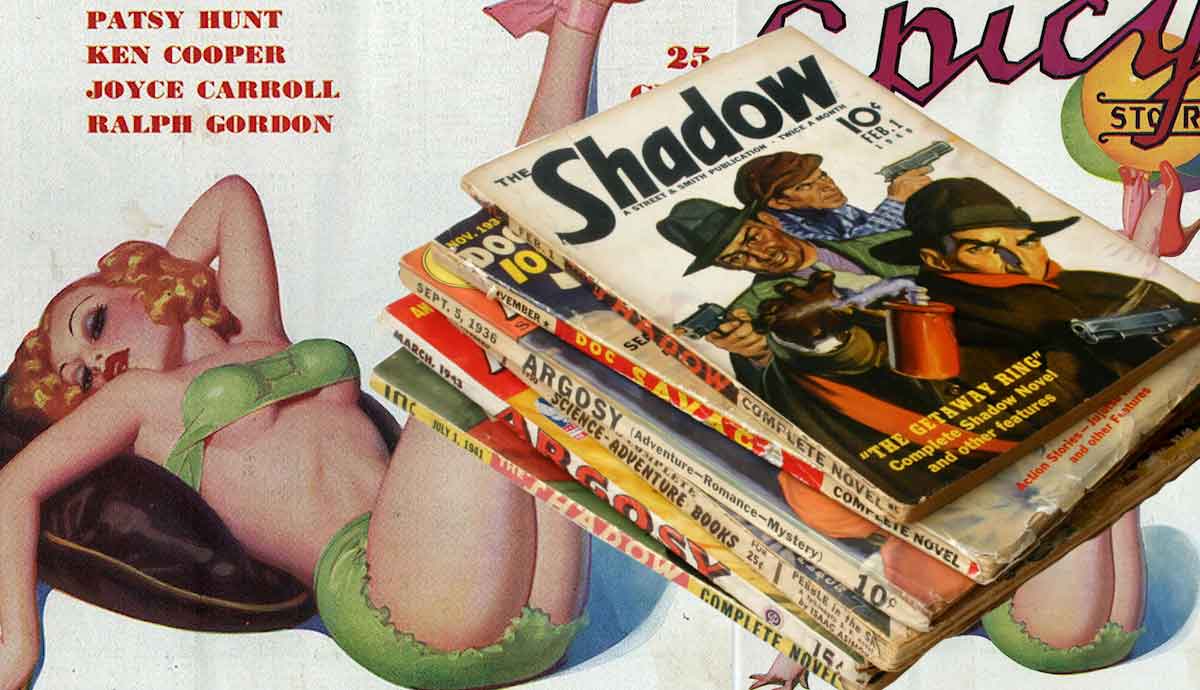

The early 20th century saw an explosion in the industry of pulp fiction. Close on the heels of The Argos’ success came other publications such as The Popular Magazine, The All-Story Magazine, Blue Book, Adventure, Black Mask, Love Story, Weird Tales, and Amazing Stories.

The stories in these pulp fiction publications were accompanied by art that was colorful, dramatic, and often sexually provocative. The lack of subtlety on the newsstands was instrumental in catching the eyes of passers-by.

A Foundation for Writers, Illustrators, & Artists

The pulp fiction industry served as a launchpad for the careers of many artists. Some disappeared into obscurity, while others went on to achieve immense fame and recognition, with their art ending up in galleries and being auctioned for millions of dollars. The art of famed N.C. Wyeth (father of Andrew Wyeth) often appeared on the cover of The Popular Magazine, which debuted in 1903.

Other famous artists who got their start through pulp fiction include J.C. Leyendecker, who painted more than 400 magazine covers, with 322 of them being for the Saturday Evening Post.

Dean Cornwell became widely successful and respected, being commissioned to paint murals on federal buildings and applying his brush to the creation of many wartime recruitment posters.

Everett Raymond Kinstler was a pulp and comic book artist who was so well respected that he painted the official portraits of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan.

Famous for his paintings and illustrations of crime and western stories, Tom Lovell worked for a host of pulp fiction agencies and ended up creating art for National Geographic.

Frank Schoonover created over 5,000 paintings, from illustrating American forces in World War I to designing covers for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Princess of Mars. Schoonover was a prolific painter who also taught, having opened his own studio.

Of course, none of this could have happened without the main content of the books. Many authors became famous through their contributions to pulp fiction. Among the most famous authors were Robert E. Howard, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Johnston McCulley, H.G. Wells, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Zane Grey, H.P. Lovecraft, Talbot Mundy, Abraham Merritt, and Horatio Alger.

Through pulp, these authors introduced us to their creations, which are still famous today. Among these creations were Robert E. Howard’s Conan, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter and Tarzan, Johnston McCulley’s Zorro, and H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, which has garnered a significant cult following and introduced the world to the genre of cosmic horror.

Other famous characters include heroes such as Biggles, Flash Gordon, Doc Savage, The Shadow, and The Phantom Detective. In their heyday, these characters were picked up by movie companies and transferred to the silver screen. Even after the demise of the pulp era, some of these characters continued to outlive the industry that spawned them. Recent examples include John Carter (2012) and Conan (2011).

An Explosion of Titles & Genres

Pulp fiction catered to every niche of the American public. Every genre had a slew of publications covering it. If westerns were your thing, you could purchase Dime Western, Exciting Western, Rio Kid Western, Star Western Texas Rangers, Thrilling Western, Western Aces, Western Story, and Wild West Weekly. There was certainly no shortage of titles to choose from!

Other genres, too, had similarly long lists of titles. For crime, you could read Dime Detective Magazine, Detective Story Magazine, Spy Stories, The Black Mask, The Shadow, Strange Detective Mysteries, and All-Story Detective.

If you wanted to lose yourself in a great adventure story, you could read Adventure Magazine, True Adventures, Jungle Stories, Doc Savage, Blue Book, and the Mysterious Wu-Fang.

Horror pulps included Dime Mystery Magazine, Terror Tales, Horror Stories, Weird Tales, and Horror Stories.

Science-fiction stories became hugely popular during this time period, and originally referred to as “fantasy,” the genre was renamed “scientifiction” in 1926 before finally being referred to as “science fiction” from 1954 onwards. Pulp publications here included Wonder Stories, Fantastic Adventures, Weird Tales, and Amazing Stories.

For sports stories, you could read Sport Story Magazine, Fight Stories, and Baseball Stories, and if you wanted to indulge in war fiction, you could read War Stories, Submarine Stories, Sky Raiders, G-8 and his Battle Aces, Daredevil Aces, American Sky Devils, and Battle Stories.

Romantic pulps such as Love Story Magazine, Romance, and New Love were particularly aimed at women.

And, of course, the list would not be complete without mentioning the erotic fiction on offer. For this, publications such as New York Nights, Cupid’s Capers, Saucy, and the “Spicy” range of magazines such as Spicy Crime, Spicy Western, and Spicy Mystery Stories.

Each genre of pulp fiction even had its own sub-genres. In the horror and crime genres, for example, there was the sub-genre of “weird-menace,” in which the antagonists were pitted against unusually sadistic villains. The stories themselves involved graphic scenes of torture and brutality. A particularly popular sub-genre was the “romance-western,” which included publications such as Rangeland Romances, Golden West Romances, Rodeo Romances, and Romantic Western.

The End of Pulp Fiction

The heydays of pulp fiction were suddenly interrupted by the Second World War. The war effort put a high demand on pulp paper, and as a result, the pulp fiction industry suffered shortages of its physical necessity for production.

In 1949, one of the major producers of pulp fiction magazines, Street & Smith, closed their pulp offices in order to focus on slicks. Many pulp magazines also transitioned to slicks, such as Argosy, Blue Book, Adventure, and Short Stories. These became “mens’ adventure” magazines, as they were known, and evolved over time to eventually become magazines such as FHM and Maxim. At this time, the pulp market also encountered competition from comic books and paperback novels. Many of pulp’s authors, artists, and editors made the transition to slicks as they sought better pay.

In the 1950s, television became cheaper and more widely available, and televised programming took over from pulp in satiating the human desire for stories. In 1957, the biggest distributor of pulp fiction magazines, American News Company, went into liquidation, and for many historians, this date signals the end of the “pulp era.”

Although the industry died, it had transformed popular opinion on many fantasy, horror, and science fiction genres. It brought what was considered “fringe” elements into the mainstream. It also provided a foundation for the careers of authors, artists, and other people attached to the industry. No less important were the characters that were portrayed, with many of them moving on with their creators into the realms of cinema, paperback novels, and comics.

Human beings have always had a built-in desire to be entertained by stories. In an age where groups of people had been separated into family units and families were separated for long hours throughout the day, the need arose for entertainment that did not involve other people.

In the earlier decades of pulp fiction, televisions were yet to be invented, and in the latter decades, they were expensive and considered a luxury item. Pulp fiction filled the gap in the market with immense amounts of literature that was consumed in vast quantities.

Today the market exists as a cult attraction, creating feelings of nostalgia for a bygone era before the advent of televised entertainment.