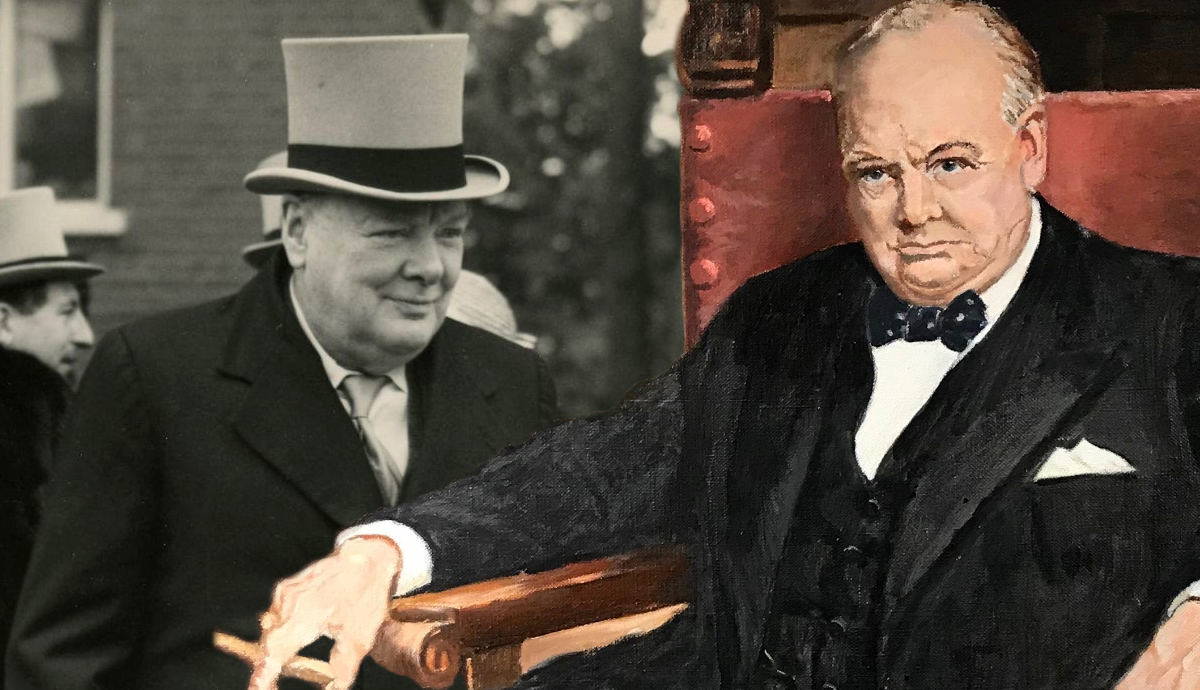

Winston Churchill is a well-known political figure who held major military and civilian positions in the British government during his long political career, including being elected as Prime Minister twice. He held the premiership of Great Britain from 1940–1945 and again from 1951–1955. Winston Churchill is recognized as an inspirational political leader who led Great Britain to victory in World War II. He is known as an outstanding orator and writer and received the Nobel Prize in 1953 for writing his six-volume history of World War II. Churchill was an excellent painter as well, and his works of art are now worth millions of dollars.

Youth & Childhood of Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill was born in 1874 at his family’s ancestral home, Blenheim Palace, in Oxfordshire, England. He was the eldest son of Lord Randolph Churchill and Lady Jennie Jerome. Even though Churchill saw himself as British, his mother was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1854 to a wealthy financier, Leonard Jerome. Lord Randolph Churchill and Lady Jannie Jarome met in Paris, France, and married in 1873. Churchill and his brother, Jack, were raised mainly in the United Kingdom, though they moved from place to place throughout their childhood and spent holidays in different European countries, including Austria-Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, and Belgium.

Winston Churchill was particularly attached to his nanny, Mrs. Elizabeth Everest, and called her “Woom” or “Woomany.” In 1893, after 18 years of service, Elizabeth Everest left her job and soon died of peritonitis in 1896. Winston Churchill grieved the death of his closest friend, referring to her as “my dearest and most intimate friend during the whole of the twenty years I had lived.” Lady Churchill played a limited role in Churchill’s early years, which might be a reason for his attachment to his nanny. Referring to his mother, Winston Churchill later stated: “I loved her dearly—but at a distance,” but as he grew older, he saw Lady Churchill as his closest friend and strongest ally.

Winston Churchill attended multiple schools but had little interest in academic excellence or discipline. According to Victorian traditions, Churchill was first sent to the boarding school of St. George in Berkshire at the age of seven, where he had poor grades and often misbehaved. Due to his poor health, Churchill moved to Brunswick School in Hove in September 1884, where he slightly improved his academic performance.

In April 1988, Winston Churchill barely passed the Harrow School exams. He was particularly interested in history and English but was still unpunctual and described as careless by his teachers. During this time, Winston Churchill found his passion in poetry and writing and published his works in the school magazine Harrovian.

Due to his poor academic performance, Churchill’s family thought he would not be able to study at the university and instead chose a military career for him. It took Churchill three attempts to pass the exams at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1893, where he spent 15 months as a cadet in the cavalry. Soon after his graduation, his father died in January 1895.

The early death of his father led Churchill to believe that his family members would die young, which did not appear to be true. Lady Churchill, who married twice after Lord Churchill’s death, died in her late sixties in 1921, while his brother, Jack Churchill, died in 1947, aged 67. Winston Churchill himself lived for 70 years after his father’s death and survived multiple strokes.

After graduating from the military college, Winston Churchill left for Cuba to report on the Cuban War of Independence for the Daily Graphic. After spending a couple of months there, his regiment was relocated to India, where Winston Churchill served both as a soldier and journalist until 1897. The Story of the Malakand Field Force, published in 1898, gained Churchill wider public attention. He started his career as an author, culminating in the publication of his romance, Savrola, in 1900. In 1899, the London Morning Post sent Winston Churchill to South Africa to cover the Boer War. He was captured just after arriving and managed to escape through a bathroom window, which made him a celebrity back in Britain.

With his background as a soldier, war correspondent, and author of six books, Winston was 30 years old and already well-known when he married Clementine Hozier. Clementine became and remained Churchill’s trusted confidante throughout his political career. According to Churchill, getting through the war years would have been “impossible without her,” not only for her efforts to preserve his health but also for influencing her husband’s political decisions.

Winston Churchill’s Political Career Before World War II

Winston Churchill began his political career at a young age, at only 25 years old. His activities in India and Cuba helped to expand his horizons. Besides observing the wars for independence, he embarked on self-education, reading works of Plato, Edward Gibbon, Charles Darwin, and Thomas Babington Macaulay, among others. As a result, in 1899, Winston Churchill left the military and decided to dedicate himself to politics. He hired a private secretary and participated in the 1900 General Elections as a Conservative candidate for the Oldham seat.

Churchill managed to secure a seat in Parliament with a narrow victory. Members of parliament were not paid at the time, so Winston Churchill embarked on lecture tours around the world to discuss his experiences in South Africa. He traveled to the United States and met President William McKinley and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. He also visited Canada and returned to Europe to give lectures in Madrid and Paris. Churchill managed to acquire a considerable amount of money to support his political endeavors.

Although Churchill was allied with the Hughligans, a conservative group, he was one of their most vocal critics regarding the level of public expenditures. Over time, Winston Churchill became more inclined toward the liberal opposition as their views aligned on key issues, such as the censure against the government’s use of indentured Chinese laborers in South Africa and voting in favor of a bill introduced by the liberals to restore legal rights to trade unions.

Churchill’s opposition to the Conservatives pushed the Oldham Conservative Association to withdraw their support of his candidacy in the election in December 1903. However, this didn’t stop Churchill from upholding his values. The opposition finally culminated on May 31, 1904, when Churchill left the Conservative Party for the Liberal Party at the House of Commons.

The Liberal Party won the 1906 general elections with 337 seats to the Conservative Party’s 157. On the request of the Manchester Liberals, Winston Churchill ran for the Manchester North West seat and was elected to the House of Commons once more.

During this time, Churchill also finished and published his father’s biography after working on it for several years. He received an advance payment of £8,000 for it, which was the highest amount ever paid for a political biography in the country at the time, which is equivalent in purchasing power to £1,244,517.44 today. In this new government, Churchill distinguished himself as the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonial Office, a position that he requested.

Churchill rose swiftly within the Liberal ranks and became a cabinet minister in 1908—President of the Board of Trade. In 1910, he served as a Home Secretary for a year, and in 1911, he was appointed the First Lord of the Admiralty. These events mark the period when Churchill shifted his focus from domestic to international politics. During this time, the world saw the rise of Germany, and Churchill saw the need to prepare Britain for future international crises. He worked on modernizing the British fleet and navy.

Nevertheless, the start of World War I was not as successful for Britain as Churchill thought. The 1915 British invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula in the Ottoman Empire, which aimed to take them out of the war, is regarded as the lowest point in his political career. Turkish forces resisted, and after nine months and 250,000 casualties, Britain was forced to withdraw. Churchill left the post and, in 1924, rejoined the Conservatives, holding different positions in the government.

During the period between World War I and World War II, Churchill was actively trying to spread awareness about the rise of German nationalism that threatened another war. Adolf Hitler declared on March 16, 1935, that he would rearm Germany in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles, which called for German disarmament following World War I in order to prevent Germany from starting a new war. Hitler announced plans to reintroduce conscription, build an army of more than 500,000 troops, and develop an aviation force. However, the previous experience of military campaigns pushed Britain toward isolationism, making it reluctant to be involved in another international conflict.

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain even signed an agreement with Adolf Hitler in 1938, granting Germany a piece of Czechoslovakia, which Churchill described as “throwing a small state to the wolves” and failing Britain’s attempts to maintain peace.

In 1939, Hitler invaded Poland, and Britain and France were forced to declare war. Chamberlain resigned, and Winston Churchill took his place on May 10, 1940.

Leadership During World War II

As Nazi Germany threatened an invasion, Winston Churchill directed his energy as Prime Minister toward increasing and modernizing British defense. He adopted the position of Minister of Defense as well. Besides taking an active role in both administrative and diplomatic tasks, he gave remarkable and memorable speeches, trying to lift and stimulate British morale in a time of great crisis.

In 1940, Germany attacked Russia, and the United States entered World War II in 1941. Thanks to Winston Churchill’s political intuition, he had already established close relations with the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and despite mistrust, he cooperated with the leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, as well. These leaders, also called the “Big Three,” met several times to discuss wartime issues, the most important of which were held in 1943 in Tehran, Iran, and Yalta, Crimea in 1945. The key outcome of the Tehran Conference was the Allies’ commitment to open a second front against Nazi Germany. While at Yalta, the Big Three agreed that Germany would be divided into four post-war occupation zones under the control of American, British, French, and Soviet military forces following its unconditional capitulation. The opening of the second front gave the Soviet Union much-needed power to fight in Eastern Europe and eventually weakened Nazi Germany. Churchill was the chief architect of these negotiations that eventually led to the victory of the Allied Forces.

In September 1945, Germany surrendered, and the war was over. In Britain, new elections were approaching, and a victorious Churchill seemed unbeatable. However, war-weary British voters did not want the Conservatives to be elected again. In the 1945 elections, Winston Churchill lost.

He continued giving public speeches on different political issues. In 1946, in the United States, he declared that “an iron curtain has descended across the continent,” once again warning about the growing dangers of the Soviet Union, which, as history shows, appeared true. He advocated for the British union with France and Germany to re-create “the European Family,” which would eventually pave the way to his idea of the “United States of Europe.” Churchill believed that only close cooperation and the unity of the English-speaking world could destroy communist tyranny.

The Post-War Political Career of Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill again ran for the post of Prime Minister and was re-elected in 1951. However, as the British politician Roy Jenkins described him, he was “gloriously unfit for office” by this time. Churchill was already 77 and in deteriorating health. He often dealt with the day-to-day tasks from his bed. Even though his decision-making and powerful personality were the same, his leadership appeared less decisive, so his influence, especially on British domestic policies, was limited.

Nevertheless, Winston Churchill never stopped trying to influence the Cold War using his personal diplomatic ties, but they were not successful. His vision of building a sustainable détente between the East and the West failed. Eventually, his poor health led him to resign on April 5, 1955. Foreign Secretary and Deputy Prime Minister Anthony Eden became the new prime minister.

“I am ready to meet my maker; whether my maker is prepared for the great ordeal of meeting me is another matter,” Winston Churchill declared on his 75th birthday. He remained a member of parliament, though he did not play an active role, finally announcing his retirement from politics in 1963.

Winston Churchill died on January 24, 1965, and was given a state funeral for his enormous contributions to the United Kingdom and the international community. He became the first non-royal to be given a state funeral since the Duke of Wellington, a leading military and political figure in 19th-century Britain who also served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

In the book Things That Matter, a collection of his newspaper columns and essays, famous American columnist Charles Krauthammer included a small chapter entitled “Winston Churchill: The Indispensable Man.” In it, he argues why Time magazine should have chosen Churchill as its “Person of the Century” in 1999:

“Because only Churchill has that absolutely necessary criterion—irreplaceability. And who is the hero of that story? Who slew the dragon [totalitarianism]? Yes, the common man—the taxpayer, the grunt—fought and won the wars. Yes, it was America and its allies. Yes, it was the great leaders: FDR, de Gaulle, Adenauer, Truman, John Paul II, Thatcher, and Reagan. But above all, victory required one man, without whom the fight would have been lost at the beginning. It required Winston Churchill.”