The Vienna Secession, which was founded in 1897, was the name of a group of male artists that wanted to break free from popular classical and historical art. They aimed to experiment with new shapes, subjects, techniques, and sizes and ultimately create a new type of art. Some Secession members, like Gustav Klimt and Otto Wagner, became famous artists. However, apart from the famous male artists, the Secession group also collaborated with various women artists. Continue reading to explore who these women were and what kind of art they created.

Women’s Right During the Vienna Secession Period

At the end of the nineteenth century, there were many discussions around the topic of identity in Vienna. As a result of the high levels of immigration that Vienna dealt with at the time, different social and ethnic groups merged, and the influx of new ideas challenged the environment. One of the most significant identity questions that this process initiated was that of the position of women. It even received its own name: die Frauenfrage, meaning the women question.

As in many other places at the time, some people in Vienna opposed women’s emancipation. Still, the last half of the nineteenth century, as well as the early twentieth century, certainly saw essential changes for women. After the erection of a national women’s rights organization in 1866, the Verein Kunstschüle für Frauen und Mädchen was founded in 1897. This was an art school for girls and women in Vienna, which allowed them to receive professional training in art and commercial design for the first time in history.

The Secession consisted of many artists who left the official Künstlergenossenschaft, an Austrian art society that supported the creation of classical and historical art. The members of the Vienna Secession wanted to break free from exactly that type of art. Moreover, apart from breaking with what they considered outdated styles, the artists also wanted to break ties with outdated social norms. Among these was the notion that women shouldn’t be allowed to form a part of an artistic movement. However, despite the fact that many artists from the Secession group were progressive, women artists were still not allowed to become official members. The reason for this, however, lay outside of the Secession group since the country’s laws didn’t permit it.

However, the Secession members did collaborate with women and allowed them to exhibit their pieces at the Viennese Secession Building. Women like Berta Zuckerkandl also wrote important sections of the Secession magazine called Ver Sacrum. Zuckerkandl also overlooked the Secession’s international relations. It’s interesting to know that Klimt’s muse and life partner Emily Flöge worked as an independent fashion designer. In 1912, Klimt created a new art movement that allowed women artists to become its official members.

The Exclusion of Female Secession Artists from Art History

There were multiple women artists that collaborated with the Vienna Secession members, but they have mostly been left out of art historical narratives about the movement. In art historical writing, the Secession’s style is often defined by the portrayal of women by Gustav Klimt. In other words, art historians seemed to have considered Klimt’s works, and in particular his woman portraits, as the definition of Secession art, thereby excluding art that did not fit into that image. It’s not strange that Klimt, as the president of the movement, was put at the forefront of narratives about the Secession.

The idea that Klimt’s paintings of women defined the Secession also creates an incomplete image of the Vienna Secession in general. Rather than for Klimt’s paintings of women alone, the Secession should be known for the wide variety of disciplines that the artists worked in. Members of the Secession include the architects and designers Joseph Olbrich, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann, the printmaker and designer Koloman Moser, and the painter and printmaker Max Kurzweil. The Secession artists believed in the union of all art forms into one big artwork called a Gesamtkunstwerk, meaning a total work of art. Therefore, seeing Klimt as the only important artist of the Secession undermines his own mission. Now, let’s take a look at some of the important women artists of the movement.

1. Broncia Koller

Broncia Koller-Pinell (1863-1934) was born in Sanok, Poland, to orthodox Jewish parents. In 1870, her father decided to immigrate to Vienna, making them one of many immigrant families of the period. Koller’s father, who was an architect of military establishments, supported his daughter in her creative endeavors. This meant that she was given the opportunity to enjoy high-quality art education. After receiving private lessons with a number of different teachers, Koller went to Munich in 1883 to study at the atelier of portrait and history painter Ludwig Heterich and landscape painting Ludwig Kühn. Looking at Koller’s oeuvre, one can see that she was taught to paint well in many different genres. In 1888, Koller started exhibiting her work. Real success followed a few years later, after exhibitions at the Künstlerhaus in Vienna in 1892, the Glaspalast in München in 1893, and the Kunstverein in Leipzig in 1894.

Around 1903, Koller met the Vienna Secession artists for the first time. From that moment on, she could often be found at the Café Museum with Josef Hoffman and Gustav Klimt. According to writer Julie M. Johnson, she would be a part of a crowd of greats. In addition, Koller’s estate in Oberwaltersdorf became a center for intellectuals, musicians, and artists, including Klimt, Moser, and Hoffman, as well as feminists Rosa Mayreder and Marie Lang.

Koller’s biggest personal achievement was exhibiting works at the Kunstschau. Kunstschau was an exhibition led by Klimt that took place in 1908 that showed pieces made by many important artists. Koller was a very serious artist whose oeuvre consisted of 367 paintings and many woodcuts. Art critics of her own time often called her a master, while colleagues were clearly inspired by her work.

Klimt’s influence is visible in Koller’s portraits. Just like Klimt, Koller used a sober background. The way she painted human skin also reminds us of Klimt. Koller took more direct inspiration from Klimt’s depiction of Genii is his Beethoven Frieze for the flying angels in her painting Orange Trees in the French Riviera.

Stylistically, Koller was influenced by Klimt’s work, but she also took inspiration from French painters like Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and George Seurat. However, Koller did not copy their style directly but subtly incorporated some stylistic elements while adding a strong personal touch. Some of the Post-impressionist and Neo-impressionist features in her works are seen through the loose and dot-like brushstrokes, the simplified abstract shapes, the use of a yellow background, and the black contours known as Cloisonnism.

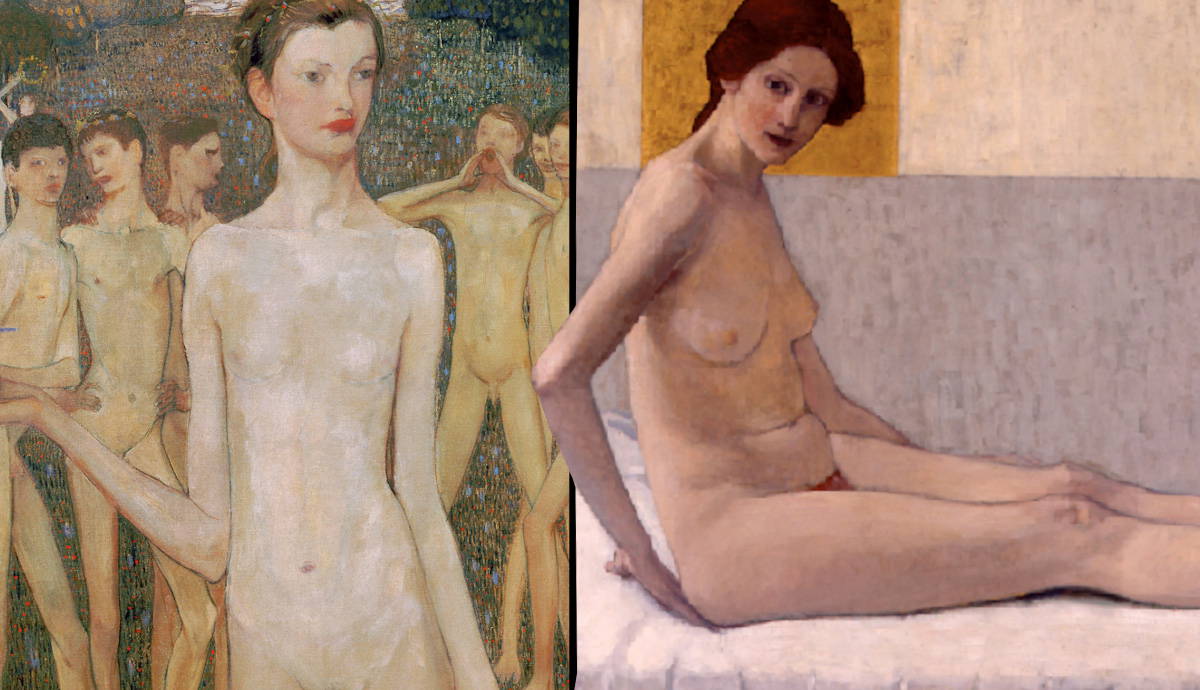

Koller painted in many different genres. Her oeuvre consists of portraits, interior scenes, nudes, landscapes, and still lifes. It was not easy for women to paint nudes, as they simply didn’t have the necessary permissions. The fact that Koller painted them anyways shows that she pushed boundaries. For her painting Seated Nude Marietta, Koller used the same model that can be seen in Klimt’s works.

2. Elena Luksch-Makowsky

Elena Luksch-Makowsky (1878-1967) was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia as the daughter of the Russian painter Constantin Makowsky. She grew up in a wealthy family, so she enjoyed an education in painting at the elite school of Princess Tenisheva. She continued her studies at the Art Academy of Saint Petersburg and finished her education at the Azbé-Schule in Munich. During her youth, Luksch-Makowsky moved from one big European city to another. Her family eventually ended up living in a summerhouse in Finland and in the French Côte d’Azur region. These journeys would make a big impact on her art.

In 1900, the now-married Luksch-Makowsky and her husband, Richard Luksch, decided to move to his native city of Vienna. Richard was a sculptor active in the art circles of Europe. In Vienna, he became a member of the Secession, giving Luksch-Makowsky direct access to the group as well. Both Luksch-Makowsky and her husband frequently exhibited their works together alongside other members of the Vienna Secession. Despite the fact that she wasn’t allowed to join the male artists officially, she told her children that she was, in fact, the first female member of the group.

Luksch-Makowsky probably came closest to being an official member. She even received a monogram block with her signature that all the male artists had. These monograms were used in exhibitions instead of signatures. Luksch-Makowsky also wrote for the magazine Ver Sacrum, played an important role in the Raumkunst exhibitions at the Secession building, and was included in the important Beethoven exhibition in 1902.

Luksch-Makowsky’s work was defined by her fascination with Russian folk tales, literature, and philosophy. She incorporated motifs from these sources into her paintings and mixed them with symbolist elements. The artist was read to a lot as a child, so she developed a life-long interest in studying characters. During her travels in Europe Luksch-Makowsky always carried a sketchbook with her to capture different people. Seeing that the stories read to her were often quite suspenseful, she also developed an unusual preference for scary themes. She aimed to create epic, suspenseful, and vibrant artworks.

The works Self-portrait with Son Peter and Death and Time are examples of her symbolist and slightly darker works. In the first painting, Luksch-Makowsky depicted herself with her baby. The painting also refers to the Secession’s motto that everything serves the holy spring (Ver Sacrum) or, in other words, new beginnings. The child represents this new spring.

However, the fact that Luksch-Makowsky’s artworks were suspenseful doesn’t mean that they were necessarily dark in color. Luksch-Makowsky also made colorful artworks like Adolescentia. This painting shows a young tall female figure in her adolescent years while she’s being watched by men. Her naked body almost fills the whole canvas.

3. Teresa Feodorovna Ries and The Vienna Secession

Teresa Feodorovna Ries (1866-1956) was born in Budapest to Jewish parents. She got married and divorced before the age of twenty. During this period, she also lost her baby. After this phase of her life, she attended the Moscow Academy of Fine Arts. She was eventually dismissed for challenging her teacher’s authority. Ries didn’t want to let this stop her from being an artist, so she emigrated to Vienna, where she convinced Edmund Hellmer to take her on as his private student. At this time, women were not yet allowed to attend the official Academy of Fine Arts.

Hellmer thought so highly of Ries’ abilities that he even asked her to secretly take over two of his commissions and make them under his name. Ries became one of Vienna’s most famous artists of the time. Her rise to fame started in 1895 when she exhibited her work Witch at the Künstlerhaus. This sculpture featured a young, naked witch clipping her toenails before Sabbath. The work was considered shocking, but the former Austrian-Hungarian emperor liked it, which helped turn it into a success. During her career, Ries also drew the attention of various well-known figures like the American writer Mark Twain, the journalist and founder of the Zionist Organisation Theodor Herzl, and the Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig.

Ries was invited to exhibit her works at the Secession building when it opened in 1897. She became the first woman to exhibit with the group. The exhibited pieces included her portraits of Prince Thurn-Taxis, Countess Elise Wilczek-Kinsky, and industrialist Bernhard Hellmann.

Ries made her sculptures from materials like bronze, marble, stone, and plaster. Some of her famous pieces include Death, Sleepwalker, The soul returns to God, Eve, and Penelope. All of these sculptures feature a nude or semi-nude figure. Ries’s sculptures show an interest in universal themes like death or dreams. Ries shared these interests with Romantic artists. She masterfully depicted skin, wavy hair, fragile states of being, and fabric.

Ries frequently organized exhibitions of her works at her studio. Members of the aristocracy, politicians and art critics attended the openings. During World War II, Ries had to flee Austria and leave her sculptures behind. Unfortunately, many of her works were lost, destroyed, or labeled as degenerate art. Fortunately, Ries wrote an autobiography, one of the most important sources of information about her life and career.